Graph theory

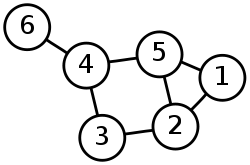

In mathematics and computer science, graph theory is the study of graphs: mathematical structures used to model pairwise relations between objects from a certain collection. A "graph" in this context refers to a collection of vertices or 'nodes' and a collection of edges that connect pairs of vertices. A graph may be undirected, meaning that there is no distinction between the two vertices associated with each edge, or its edges may be directed from one vertex to another; see graph (mathematics) for more detailed definitions and for other variations in the types of graphs that are commonly considered. The graphs studied in graph theory should not be confused with "graphs of functions" and other kinds of graphs.

Graphs are one of the prime objects of study in Discrete Mathematics. Refer to Glossary of graph theory for basic definitions in graph theory.

Contents |

History

The paper written by Leonhard Euler on the Seven Bridges of Königsberg and published in 1736 is regarded as the first paper in the history of graph theory.[1] This paper, as well as the one written by Vandermonde on the knight problem, carried on with the analysis situs initiated by Leibniz. Euler's formula relating the number of edges, vertices, and faces of a convex polyhedron was studied and generalized by Cauchy[2] and L'Huillier,[3] and is at the origin of topology.

More than one century after Euler's paper on the bridges of Königsberg and while Listing introduced topology, Cayley was led by the study of particular analytical forms arising from differential calculus to study a particular class of graphs, the trees. This study had many implications in theoretical chemistry. The involved techniques mainly concerned the enumeration of graphs having particular properties. Enumerative graph theory then rose from the results of Cayley and the fundamental results published by Pólya between 1935 and 1937 and the generalization of these by De Bruijn in 1959. Cayley linked his results on trees with the contemporary studies of chemical composition.[4] The fusion of the ideas coming from mathematics with those coming from chemistry is at the origin of a part of the standard terminology of graph theory.

In particular, the term "graph" was introduced by Sylvester in a paper published in 1878 in Nature, where he draws an analogy between "quantic invariants" and "co-variants" of algebra and molecular diagrams:[5]

- "[...] Every invariant and co-variant thus becomes expressible by a graph precisely identical with a Kekuléan diagram or chemicograph. [...] I give a rule for the geometrical multiplication of graphs, i.e. for constructing a graph to the product of in- or co-variants whose separate graphs are given. [...]" (italics as in the original).

One of the most famous and productive problems of graph theory is the four color problem: "Is it true that any map drawn in the plane may have its regions colored with four colors, in such a way that any two regions having a common border have different colors?" This problem was first posed by Francis Guthrie in 1852 and its first written record is in a letter of De Morgan addressed to Hamilton the same year. Many incorrect proofs have been proposed, including those by Cayley, Kempe, and others. The study and the generalization of this problem by Tait, Heawood, Ramsey and Hadwiger led to the study of the colorings of the graphs embedded on surfaces with arbitrary genus. Tait's reformulation generated a new class of problems, the factorization problems, particularly studied by Petersen and Kőnig. The works of Ramsey on colorations and more specially the results obtained by Turán in 1941 was at the origin of another branch of graph theory, extremal graph theory.

The four color problem remained unsolved for more than a century. In 1969 Heinrich Heesch published a method for solving the problem using computers[6]. A computer-aided proof produced in 1976 by Kenneth Appel and Wolfgang Haken makes fundamental use of the notion of "discharging" developed by Heesch[7][8]. The proof involved checking the properties of 1,936 configurations by computer, and was not fully accepted at the time due to its complexity. A simpler proof considering only 633 configurations was given twenty years later by Robertson, Seymour, Sanders and Thomas.[9]

The autonomous development of topology from 1860 and 1930 fertilized graph theory back through the works of Jordan, Kuratowski and Whitney. Another important factor of common development of graph theory and topology came from the use of the techniques of modern algebra. The first example of such a use comes from the work of the physicist Gustav Kirchhoff, who published in 1845 his Kirchhoff's circuit laws for calculating the voltage and current in electric circuits.

The introduction of probabilistic methods in graph theory, especially in the study of Erdős and Rényi of the asymptotic probability of graph connectivity, gave rise to yet another branch, known as random graph theory, which has been a fruitful source of graph-theoretic results.

Drawing graphs

Graphs are represented graphically by drawing a dot for every vertex, and drawing an arc between two vertices if they are connected by an edge. If the graph is directed, the direction is indicated by drawing an arrow.

A graph drawing should not be confused with the graph itself (the abstract, non-visual structure) as there are several ways to structure the graph drawing. All that matters is which vertices are connected to which others by how many edges and not the exact layout. In practice it is often difficult to decide if two drawings represent the same graph. Depending on the problem domain some layouts may be better suited and easier to understand than others.

Graph-theoretic data structures

There are different ways to store graphs in a computer system. The data structure used depends on both the graph structure and the algorithm used for manipulating the graph. Theoretically one can distinguish between list and matrix structures but in concrete applications the best structure is often a combination of both. List structures are often preferred for sparse graphs as they have smaller memory requirements. Matrix structures on the other hand provide faster access for some applications but can consume huge amounts of memory.

List structures

- Incidence list

- The edges are represented by an array containing pairs (tuples if directed) of vertices (that the edge connects) and possibly weight and other data. Vertices connected by an edge are said to be adjacent.

- Adjacency list

- Much like the incidence list, each vertex has a list of which vertices it is adjacent to. This causes redundancy in an undirected graph: for example, if vertices A and B are adjacent, A's adjacency list contains B, while B's list contains A. Adjacency queries are faster, at the cost of extra storage space.

Matrix structures

- Incidence matrix

- The graph is represented by a matrix of size |V| (number of vertices) by |E| (number of edges) where the entry [vertex, edge] contains the edge's endpoint data (simplest case: 1 - incident, 0 - not incident).

- Adjacency matrix

- This is an n by n matrix A, where n is the number of vertices in the graph. If there is an edge from a vertex x to a vertex y, then the element

is 1 (or in general the number of xy edges), otherwise it is 0. In computing, this matrix makes it easy to find subgraphs, and to reverse a directed graph.

is 1 (or in general the number of xy edges), otherwise it is 0. In computing, this matrix makes it easy to find subgraphs, and to reverse a directed graph. - Laplacian matrix or Kirchhoff matrix or Admittance matrix

- This is defined as D − A, where D is the diagonal degree matrix. It explicitly contains both adjacency information and degree information. (However, there are other, similar matrices that are also called "Laplacian matrices" of a graph.)

- Distance matrix

- A symmetric n by n matrix D whose element

is the length of a shortest path between x and y; if there is no such path

is the length of a shortest path between x and y; if there is no such path  = infinity. It can be derived from powers of A

= infinity. It can be derived from powers of A ![d_{x,y}=\min\{n\mid A^n[x,y]\ne 0\}. \,](/2010-wikipedia_en_wp1-0.8_orig_2010-12/I/b8115a468b15e0c1b352c92574573415.png)

Problems in graph theory

Enumeration

There is a large literature on graphical enumeration: the problem of counting graphs meeting specified conditions. Some of this work is found in Harary and Palmer (1973).

Subgraphs, induced subgraphs, and minors

A common problem, called the subgraph isomorphism problem, is finding a fixed graph as a subgraph in a given graph. One reason to be interested in such a question is that many graph properties are hereditary for subgraphs, which means that a graph has the property if and only if all subgraphs have it too. Unfortunately, finding maximal subgraphs of a certain kind is often an NP-complete problem.

- Finding the largest complete graph is called the clique problem (NP-complete).

A similar problem is finding induced subgraphs in a given graph. Again, some important graph properties are hereditary with respect to induced subgraphs, which means that a graph has a property if and only if all induced subgraphs also have it. Finding maximal induced subgraphs of a certain kind is also often NP-complete. For example,

- Finding the largest edgeless induced subgraph, or independent set, called the independent set problem (NP-complete).

Still another such problem, the minor containment problem, is to find a fixed graph as a minor of a given graph. A minor or subcontraction of a graph is any graph obtained by taking a subgraph and contracting some (or no) edges. Many graph properties are hereditary for minors, which means that a graph has a property if and only if all minors have it too. A famous example:

- A graph is planar if it contains as a minor neither the complete bipartite graph

(See the Three-cottage problem) nor the complete graph

(See the Three-cottage problem) nor the complete graph  .

.

Another class of problems has to do with the extent to which various species and generalizations of graphs are determined by their point-deleted subgraphs, for example:

- The reconstruction conjecture

Graph coloring

Many problems have to do with various ways of coloring graphs, for example:

- The four-color theorem

- The strong perfect graph theorem

- The Erdős–Faber–Lovász conjecture (unsolved)

- The total coloring conjecture (unsolved)

- The list coloring conjecture (unsolved)

- The Hadwiger conjecture (graph theory) (unsolved)

Route problems

- Hamiltonian path and cycle problems

- Minimum spanning tree

- Route inspection problem (also called the "Chinese Postman Problem")

- Seven Bridges of Königsberg

- Shortest path problem

- Steiner tree

- Three-cottage problem

- Traveling salesman problem (NP-complete)

Network flow

There are numerous problems arising especially from applications that have to do with various notions of flows in networks, for example:

- Max flow min cut theorem

Visibility graph problems

- Museum guard problem

Covering problems

Covering problems are specific instances of subgraph-finding problems, and they tend to be closely related to the clique problem or the independent set problem.

- Set cover problem

- Vertex cover problem

Graph classes

Many problems involve characterizing the members of various classes of graphs. Overlapping significantly with other types in this list, this type of problem includes, for instance:

- Enumerating the members of a class

- Characterizing a class in terms of forbidden substructres

- Ascertaining relationships among classes (e.g., does one property of graphs imply another)

- Finding efficient algorithms to decide membership in a class

- Finding representations for members of a class

Applications

Graphs are among the most ubiquitous models of both natural and human-made structures. They can be used model many types of relations and process dynamics in physical, biological and social systems. Many problems of practical interest can be represented by graphs.

In computer science, graphs are used to represent networks of communication, data organization, computational devices, the flow of computation, etc. One practical example: The link structure of a website could be represented by a directed graph. The vertices are the web pages available at the website and a directed edge from page A to page B exists if and only if A contains a link to B. A similar approach can be taken to problems in travel, biology, computer chip design, and many other fields. The development of algorithms to handle graphs is therefore of major interest in computer science. There, the transformation of graphs is often formalized and represented by graph rewrite systems. They are either directly used or properties of the rewrite systems(e.g. confluence) are studied.

Graph theory is also used to study molecules in chemistry and physics. In condensed matter physics, the three dimensional structure of complicated simulated atomic structures can be studied quantitatively by gathering statistics on graph-theoretic properties related to the topology of the atoms. For example, Franzblau's shortest-path (SP) rings. In chemistry a graph makes a natural model for a molecule, where vertices represent atoms and edges bonds. This approach is especially used in computer processing of molecular structures, ranging from chemical editors to database searching. In statistical physics, graphs can represent local connections between interacting parts of a system, as well as the dynamics of a physical process on such systems.

Graph theory is also widely used in sociology as a way, for example, to measure actors' prestige or to explore diffusion mechanisms, notably through the use of social network analysis software.

Likewise, graph theory is useful in biology and conservation efforts where a vertex can represent regions where certain species exist (or habitats) and the edges represent migration paths, or movement between the regions. This information is important when looking at breeding patterns or tracking the spread of disease, parasites or how changes to the movement can affect other species.

In mathematics, graphs are useful in geometry and certain parts of topology, e.g. Knot Theory. Algebraic graph theory has close links with group theory.

A graph structure can be extended by assigning a weight to each edge of the graph. Graphs with weights, or weighted graphs, are used to represent structures in which pairwise connections have some numerical values. For example if a graph represents a road network, the weights could represent the length of each road.

A digraph with weighted edges in the context of graph theory is called a network. Network analysis have many practical applications, for example, to model and analyze traffic networks. Applications of network analysis split broadly into three categories:

- First, analysis to determine structural properties of a network, such as the distribution of vertex degrees and the diameter of the graph. A vast number of graph measures exist, and the production of useful ones for various domains remains an active area of research.

- Second, analysis to find a measurable quantity within the network, for example, for a transportation network, the level of vehicular flow within any portion of it.

- Third, analysis of dynamical properties of networks.

See also

- Gallery of named graphs

- Glossary of graph theory

- List of graph theory topics

- Publications in graph theory

Related topics

- Graph property

- Algebraic graph theory

- Conceptual graph

- Data structure

- Disjoint-set data structure

- Entitative graph

- Existential graph

- Graph data structure

- Graph algebras

- Graph automorphism

- Graph coloring

- Graph database

- Graph drawing

- Graph equation

- Graph rewriting

- Intersection graph

- Logical graph

- Loop

- Null graph

- Perfect graph

- Quantum graph

- Spectral graph theory

- Strongly regular graphs

- Symmetric graphs

- Tree data structure

Algorithms

- Bellman-Ford algorithm

- Dijkstra's algorithm

- Ford-Fulkerson algorithm

- Kruskal's algorithm

- Nearest neighbour algorithm

- Prim's algorithm

- Depth-first search

- Breadth-first search

Subareas

- Algebraic graph theory

- Geometric graph theory

- Extremal graph theory

- Probabilistic graph theory

- Topological graph theory

Related areas of mathematics

- Combinatorics

- Group theory

- Knot theory

- Ramsey theory

Generalizations

- Hypergraph

- Abstract simplicial complex

Prominent graph theorists

- Berge, Claude

- Bollobás, Béla

- Chung, Fan

- Dirac, Gabriel Andrew

- Erdős, Paul

- Euler, Leonhard

- Faudree, Ralph

- Golumbic, Martin

- Graham, Ronald

- Harary, Frank

- Heawood, Percy John

- Kőnig, Dénes

- Lovász, László

- Nešetřil, Jaroslav

- Rényi, Alfréd

- Ringel, Gerhard

- Robertson, Neil

- Seymour, Paul

- Szemerédi, Endre

- Thomas, Robin

- Thomassen, Carsten

- Turán, Pál

- Tutte, W. T.

Notes

- ↑ Biggs, N.; Lloyd, E. and Wilson, R. (1986), Graph Theory, 1736-1936, Oxford University Press

- ↑ Cauchy, A.L. (1813), "Recherche sur les polyèdres - premier mémoire", Journal de l'Ecole Polytechnique 9 (Cahier 16): 66–86.

- ↑ L'Huillier, S.-A.-J. (1861), "Mémoire sur la polyèdrométrie", Annales de Mathématiques 3: 169–189.

- ↑ Cayley, A. (1875), "Ueber die Analytischen Figuren, welche in der Mathematik Bäume genannt werden und ihre Anwendung auf die Theorie chemischer Verbindungen", Berichte der deutschen Chemischen Gesellschaft 8: 1056–1059, doi:10.1002/cber.18750080252.

- ↑ John Joseph Sylvester (1878), Chemistry and Algebra. Nature, volume 17, page 284. doi:10.1038/017284a0. Online version accessed on 2009-12-30.

- ↑ Heinrich Heesch: Untersuchungen zum Vierfarbenproblem. Mannheim: Bibliographisches Institut 1969.

- ↑ Appel, K. and Haken, W. (1977), "Every planar map is four colorable. Part I. Discharging", Illinois J. Math. 21: 429–490.

- ↑ Appel, K. and Haken, W. (1977), "Every planar map is four colorable. Part II. Reducibility", Illinois J. Math. 21: 491–567.

- ↑ Robertson, N.; Sanders, D.; Seymour, P. and Thomas, R. (1997), "The four color theorem", Journal of Combinatorial Theory Series B 70: 2–44, doi:10.1006/jctb.1997.1750.

References

- Berge, Claude (1958), Théorie des graphes et ses applications, Collection Universitaire de Mathématiques, II, Paris: Dunod. English edition, Wiley 1961; Methuen & Co, New York 1962; Russian, Moscow 1961; Spanish, Mexico 1962; Roumanian, Bucharest 1969; Chinese, Shanghai 1963; Second printing of the 1962 first English edition, Dover, New York 2001.

- Biggs, N.; Lloyd, E.; Wilson, R. (1986), Graph Theory, 1736–1936, Oxford University Press.

- Bondy, J.A.; Murty, U.S.R. (2008), Graph Theory, Springer, ISBN 978-1-84628-969-9.

- Chartrand, Gary (1985), Introductory Graph Theory, Dover, ISBN 0-486-24775-9.

- Gibbons, Alan (1985), Algorithmic Graph Theory, Cambridge University Press.

- Golumbic, Martin (1980), Algorithmic Graph Theory and Perfect Graphs, Academic Press.

- Harary, Frank (1969), Graph Theory, Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

- Harary, Frank; Palmer, Edgar M. (1973), Graphical Enumeration, New York, NY: Academic Press.

- Mahadev, N.V.R.; Peled, Uri N. (1995), Threshold Graphs and Related Topics, North-Holland.

External links

Online textbooks

- Graph Theory with Applications (1976) by Bondy and Murty

- Phase Transitions in Combinatorial Optimization Problems, Section 3: Introduction to Graphs (2006) by Hartmann and Weigt

- Digraphs: Theory Algorithms and Applications 2007 by Jorgen Bang-Jensen and Gregory Gutin

- Graph Theory, by Reinhard Diestel